Last Saturday, we spent the afternoon in downtown Los Angeles. Our main motivation was to see the exhibition of MOCA's greatest hits. We all enjoyed the pre-1979 collection at the main museum space. But the post 1979 work at the Geffen Contemporary (aka the Temporary Contemporary), was very uneven. Iris was so disturbed by the warped Christmas tree forest and bloody Santa, she ran out of the gallery in tears.

We took the free shuttle back to the main museum and poked fun at bad modern art to try to put her at ease. Iris and Mark then happily walked off to TCBY and the LA Main Public Library while I took the shuttle back to visit the Japanese American National Museum. The Textured Lives exhibit was so disturbing, it was my turn to cry.

I am a fan of the Sri Threads blog, written by Stephen Szczepanek, whom I have blogged about in When the Everyday Becomes Art. He collects and sells Japanese folk textiles. He has a beautiful and highly informative blog. He introduced me to Okinawan Bashofu, woven from the fibers of the banana leaves, and Kudzu fiber cloth. These are highly labor-intensive and gorgeous fabrics that you don't see every day.

So, it was with a light heart and fibery anticipation that I set off to see the Textured Lives exhibit. I took a few photos (w/o a flash!) before a lady in the gallery told me to put my camera away.

There really weren't many textiles for an exhibit about textiles. It was only at the end of the exhibit that I saw a video with the curator of the show, Barbara F. Kawakami, that I realized that the show is not about textiles. Textiles were only a way for her to get the survivors of the Hawaiian sugar plantations to speak about a horrible chapter in their lives that they would like to forget.

One of my fellow grad school classmates at CU Boulder grew up in Torrance; her mother worked in my company (in the same satellite program where I started!) and her grandparents worked on a Maui sugar plantation. I had heard about the difficult living conditions for the plantation workers from her.

She spent summer vacations as a child with her grandmother in Maui, living in an old plantation shack. She said that, after seeing where her parents came from, she never complained about conditions in her home in Torrance.

Her mom told me about how, when she was a working mom in the 1970s, there was no such thing as day care. When school was out, she had little choice but to send her kids to her mom. My first day at my first 'real' job, my friend's mom came over to my desk to introduce herself and tell me where I could find her in case I needed anything.

Anyway, time to quit digressing.

I had also learned from an article (or was it from the book, The Language Instinct?) about the origin of Hawaiian pidgin. Plantation work crews were never more than 25% of one ethnic group because the plantation owners believed that rebellion and unionization was less likely if the workers could not communicate with one another.

What was there to rebel against? OMG, where do I start? The exhibit starts with an example of a work contract and a timeline of how many workers came, and under what kinds of conditions. At first, it started out decently, when the program was run by the government. Workers came out for 3 year contracts, worked in the fields for 10 hour days, 26 days a month; and were paid $15/month (not a bad wage in the early 20th century). After their contracts were up, the men could return home with a good nest egg.

It was after that 'trial' period, when the private contractors took over, that the system became exploitative. The new contracts still paid $15/month, but required the men to pay for passage out of their pay. It looked like a reasonable deal, until they got to the islands (a 12-14 day sea voyage) and learned that their pay was docked for every possible thing. Food, lodging, clothing all cost exorbitant amounts because the plantation owners set the prices. Basic work gear like a hat cost 75 cents! It took some people 30 years to save enough money for passage home--if they survived at all.

The sample contract also states that, if a man's wife worked, she would get $10/month. Out of loneliness and desperation, men sent away for 'picture brides', often by using the pictures of younger men. Some of these picture brides came willingly, others had their pictures sent without their knowledge by their fathers. All would become trapped, just like their husbands.

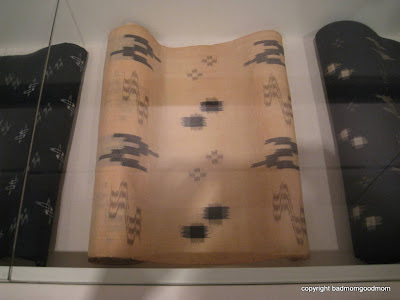

The world that they came to was so different than what they expected! You can really see that in the three rolls of Bashofu at the beginning of the exhibit. The bride brought a trousseau of fabrics that she had dyed and woven to sew clothes for her new life. She ended up never having the time to sew them up.

Women woke up at 3 AM to cook breakfast before they headed into the fields to work 10 hours, just like the men. After the fields, they cooked dinner, laundered, and foraged for food so that they wouldn't have to buy it from the plantation stores. They wound their obis tightly so that the hunger pangs were more bearable. And they mended the clothing. Sugar cane leaves are sharp and will slice through just about everything. There was always mending to do.

Many of the clothes can be seen only in photographs because they have long since been used up and worn out. One wedding dress, seen only in a photo, was refashioned into an outfit for working in the fields. She had spun, dyed and woven the fiber for her wedding kimono, only to have to cut it up for work clothing in the fields. She didn't have the money to buy any other fabric.

Heartbreaking.

If you are in the LA area, I highly, highly recommend you see this

exhibit. Though the original artifacts are meager, the oral histories in the exhibit and the

book are fantastic. There are also many faithful reproductions. There is no excuse to miss the exhibit; admission is free on Saturday, July 17, 2010. See it before it closes on August 22, 1010.

The Contest

Author, curator, collector and donor Barbara Kawakami said that studying textiles helped her earn entree into the lives of the survivors. None of them wanted to talk about plantation life at first. But she would ask them about the textiles; they would talk first about the textiles, and then continue talking about their lives at the time they made or wore them.

Ms Kawakami had an interesting life, too. She left school early due to lack of family funds, apprenticed with a dressmaker, and worked while raising a family until, at age 53, she went back to school to earn a GED and a bachelor's in textiles and a master's in history. Her senior thesis project was the genesis for this project. She traveled all over the islands and to Japan to interview the survivors she wrote about in Japanese Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii 1885-1941. She wrote a fantastic book using textiles to tie the stories together.

Because I am in a male-dominated field, one of the first things I do when I hit a new town is to join textiles groups to meet other women. Quilt guilds, American Sewing Guild, American Knitting Guild, the Embroiderer's Guild--I used to join anything that met at a convenient location and time (pre-motherhood). The oral histories I have collected in knitting and sewing circles have been priceless. I learned so much from the South Bay Quilters' Guild; this place felt like home immediately.

Write down a fiber-related oral history that you collected in a comment, or leave a comment with a link to your blog entry. At the end of August (23:59 PDT Aug 31, 2010 for you sticklers), I will select a winner and send them a copy of Japanese

Immigrant Clothing in Hawaii 1885-1941. But I think you should all see the exhibit and buy your own copy; push her amazon ranking way, way up.

Here's the Okinawan bashofu from the exhibit. The bride had harvested, spun, dyed and woven the threads.

You're making me feel like buying a plane ticket just for this show :-). Have you ever read Ronald Takaki's excellent book 'Pau Hana: plantation life and labor in Hawaii'? There is also a fair amount of biographical materials on picture brides, most of whom of course led very hard lives, but luckily were often very strong women to begin with..

ReplyDeleteI completely agree with you about the wonderful aspects of using textiles to get in touch with women in a new location. THis works even better when traveling. I had read a report by a woman who spun her way through the Greek isles, so I was prepared with a travel project, a pair of ordinary socks, when I went to the Czek Republic in the very early 90s. Economics made separation of tourists and locals very stark, and my sister and I would normally have had no contact whatsoever with locals. But sitting in parks knitting brought the old ladies out of the woodwork in droves. None of us spoke any common languages, these were not the German-speaking waiters, but we got into long exchanges about the bamboo needles, the self-striping yarn, the techniques whether continental knitting or EZ heel-turning... Much of it was clearly from women who'd survived through wwii and its aftermath by making the clothes for their entire family, and they were feeling very intent on teaching a comparatively young one how to do things right. But mostly they were amazed that a western woman knew how to do that stuff at all, much less still practiced it. There was no need for languages as we passed the socks back and forth and pointed and demonstrated. Slowest pair of socks I ever finished though :-)..

I'm definitely planning on bringing a spindle when I make it to North Africa soon, that should get women talking to me faster than anything else (I understand the older generation still largely spins right now). Spinning is even better at flushing out the old ladies than other fiber work. I've been demonstrating spinning at bring-the-sheep-up-the-mountains events in the spring, in the Pyrenees, and the only people who even know what I'm doing are older women, who talk about spinning as children during the war, and usually proclaim how happy they were to stop afterwards. But hey, the kids are interested :-).

Marie-Christine, you win! Email me your snailmail address to claim your prize.

ReplyDelete